History of the Atlantic Slave Trade

The history and origins of the Atlantic slave trade

During the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the idea that human beings were born equal and had the right to freedom and decent treatment was not widely held.

It was assumed by many that inequality, suffering and slavery were part of the natural order of things ordained by God and justified in the Christian Bible.

Slavery had long existed in both Africa and Europe. But by the late seventeenth century the rise of the capitalist system, based on trading for profit, had transformed the Atlantic trade in enslaved Africans into something different from traditional slavery.

The trade in enslaved Africans to the Americas, begun by the Portuguese and taken up by other European states, was on a new scale.

It was vast and impersonal, treating people as if they were cash goods and transporting them in huge numbers over long distances. The trade directly stimulated the growth of racialist theory in order to justify the enslavement of Africans.

The late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw a series of wars through which the British established their control over the Atlantic trade and much of the Caribbean and North America.

In this era of military and economic ‘adventuring’, ethical questions were often brushed aside or condemned as unpatriotic.

The transatlantic slave trade was essentially a triangular route from Europe to Africa, to the Americas and then back to Europe – known as the “Golden Triangle”.

On the first leg the merchants, exported goods to Africa in return for enslaved Africans, gold, ivory and spices.

The ships then travelled to the Americas – “The Middle Passage” – where the Africans were sold for sugar, tobacco and cotton. The ships then returned to Bristol, Liverpool or London laden with goods.

Britain was one of the most successful slave-trading nations and together with Portugal accounted for some 70% of all Africans transported to the Americas.

It is estimated that in the period 1640 – 1807 Britain transported 3.1 million Africans into lives of slavery.

The role of Africans in the slave trade

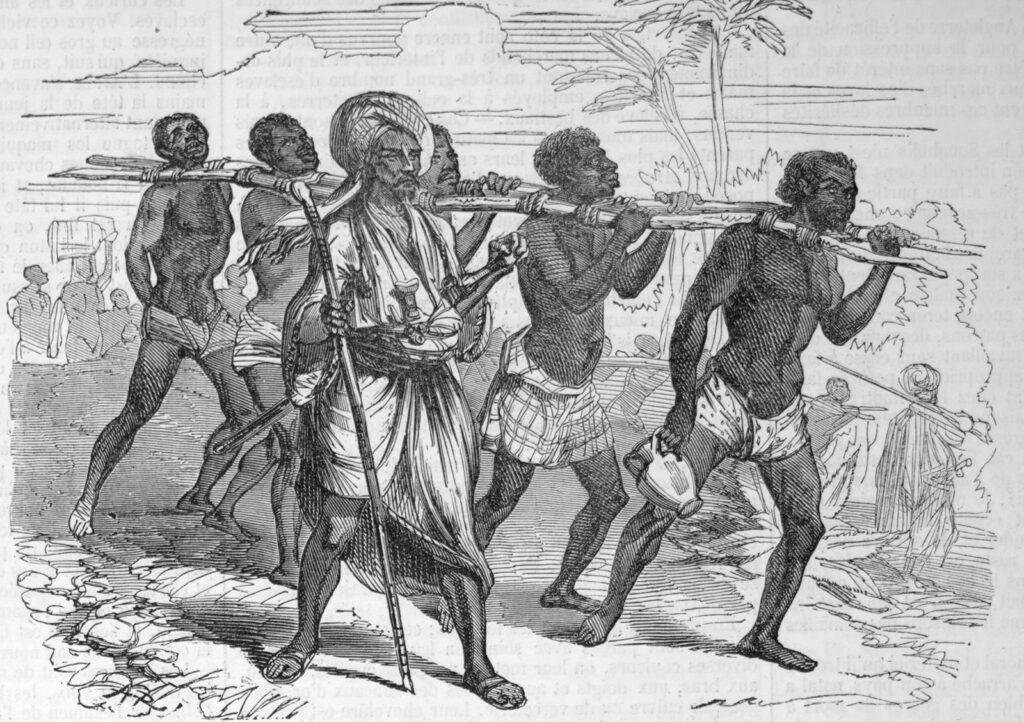

Slavery was prevalent in many west and central African societies before and during the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

During conflicts between various tribal factions individuals from one African group regularly enslaved their captors.

As the trans-Atlantic slave trade expanded, areas in West and Central Africa experienced the pressure of greater demand for enslaved labour.

This coincided with the rise of plantation agriculture in the Americas which needed a greater number of slaves.

In 1734, a British sea captain, William Snelgrave observed that Africans had been trafficking slaves long before the Europeans arrived.

He explained that Africans could be enslaved in their native country for many crimes committed like unpaid debts, also parents could “sell” their children into slavery.

However the most common source of slavery was the taking of captives during tribal wars.

The discovery of the Americas and the increased demand for the labour-intensive production of sugar led to an increased European demand for slaves, and Africa provided the perfect solution.

Not only was it close to the trade routes going west to the Americas, but it also had a pre-existing system of slavery that facilitated the trade.

Business-savvy African merchants and rulers knew they held a product highly valued by Europeans and adjusted their price accordingly.

Some demanded cowry shells for their slaves; others requested European goods such as rum, tobacco, guns, iron bars, axes, knives, and textiles.

These goods enhanced the prestige of their African owners while also providing a military advantage over their rivals.

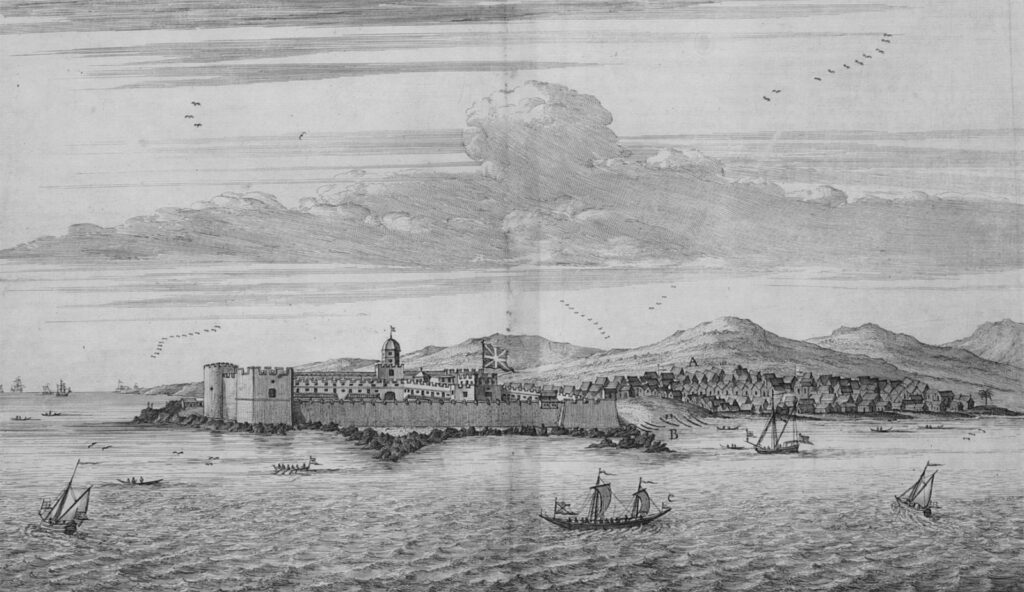

A typical slave-trading venture might begin with a European ship captain, before his departure, obtaining from his government the necessary permissions and paying the necessary fees to trade in slaves.

He would hire a crew and check the local ports for men returning from Africa to ascertain the current value of slaves and the goods African traders sought.

After purchasing supplies and desired trade items, he would set sail for the African coast.

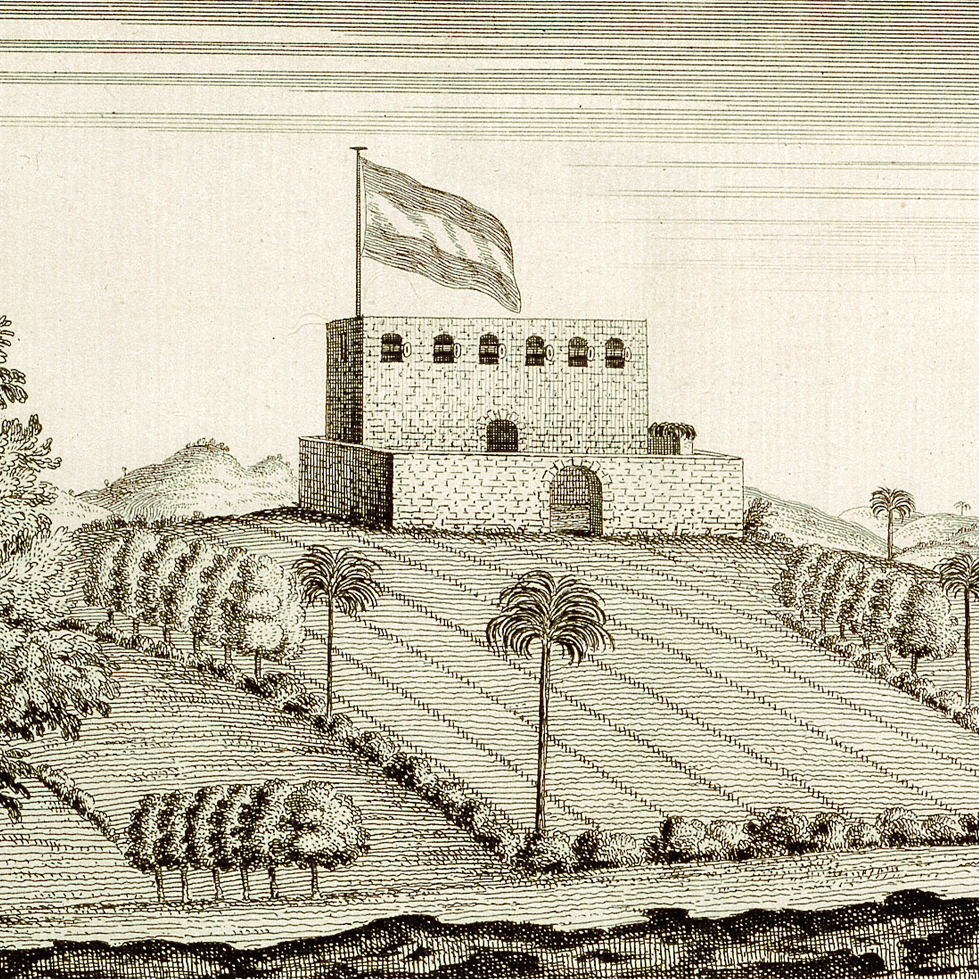

For their part, African rulers and merchants would acquire slaves, often through violent raids, and bring them to coastal forts, such as the one shown below, to be held until they were purchased by Europeans.

How British cities prospered through the slave trade

The British economy was transformed by the Atlantic slave trade.

In 1700, 80 per cent of British trade went to Europe from ports on the east and south coasts.

By 1800, 60 per cent of British trade went to Africa and America, sailing from the three main west coast ports – Glasgow, Liverpool and Bristol.

Ports such as London, Bristol and Liverpool prospered as a direct result of involvement in the slave trade.

Other ports, such as Glasgow, profited from the tobacco trade. Thousands of jobs were created in Britain supplying goods and services to slave traders.

In a period that saw Britain industrialise, profits could be made by exporting manufactured British goods to Africa and then further profits accrued from imported products made using enslaved labour, such as sugar, which became very fashionable with the British people.

The slave trade was important in the development of the wider economy – financial, commercial, legal and insurance institutions all emerged to support the activities of the slave trade.

Some merchants became bankers and many new businesses were financed by profits made from slave trading.

The slave trade played an important role in providing British industry with access to raw materials. This contributed to the increased production of manufactured goods.

Crossing the Atlantic

The Middle Passage

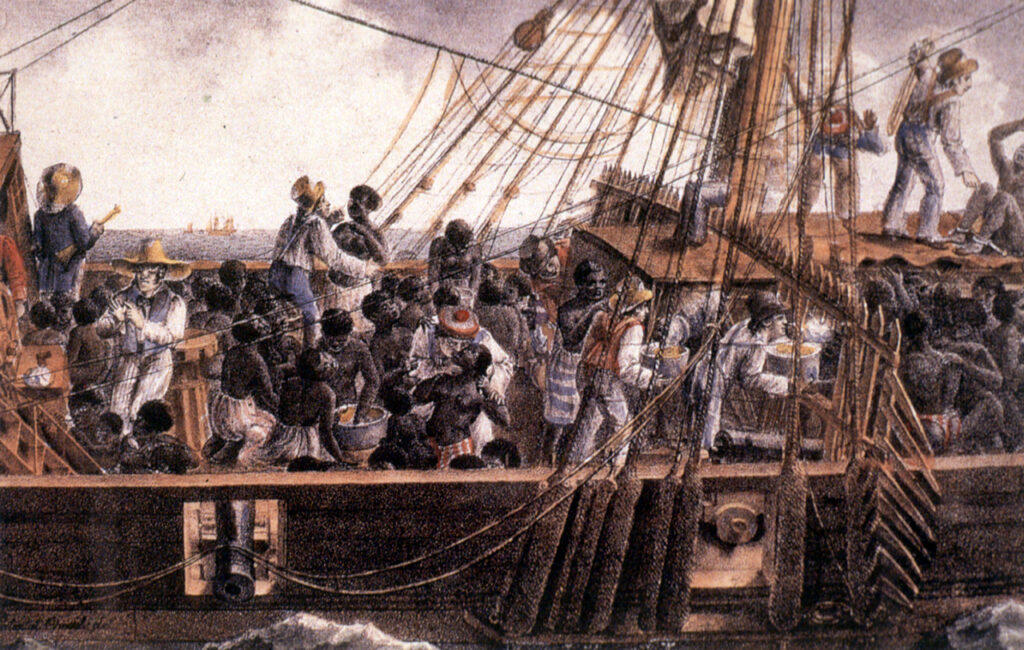

The voyage from Africa to the New World of the Americas was called the Middle Passage.

Slave ships usually took between six and eleven weeks to complete the voyage.

Conditions on board ship during the Middle Passage were appalling. The men were packed together below deck and were secured by leg irons. The space was so cramped they were forced to crouch or lie down.

Women and children were kept in separate quarters, sometimes on deck, allowing them limited freedom of movement, but this also exposed them to violence and sexual abuse from the crew.

The air in the hold was foul and putrid. Seasickness was common and the heat was oppressive. The lack of sanitation and suffocating conditions meant there was a constant threat of disease. Epidemics of fever, dysentery (the 'flux') and smallpox were frequent. Captives endured these conditions for about two months, sometimes longer.

In good weather the captives were brought on deck in midmorning and forced to exercise. They were fed twice a day and those refusing to eat were force-fed. Those who died were thrown overboard.

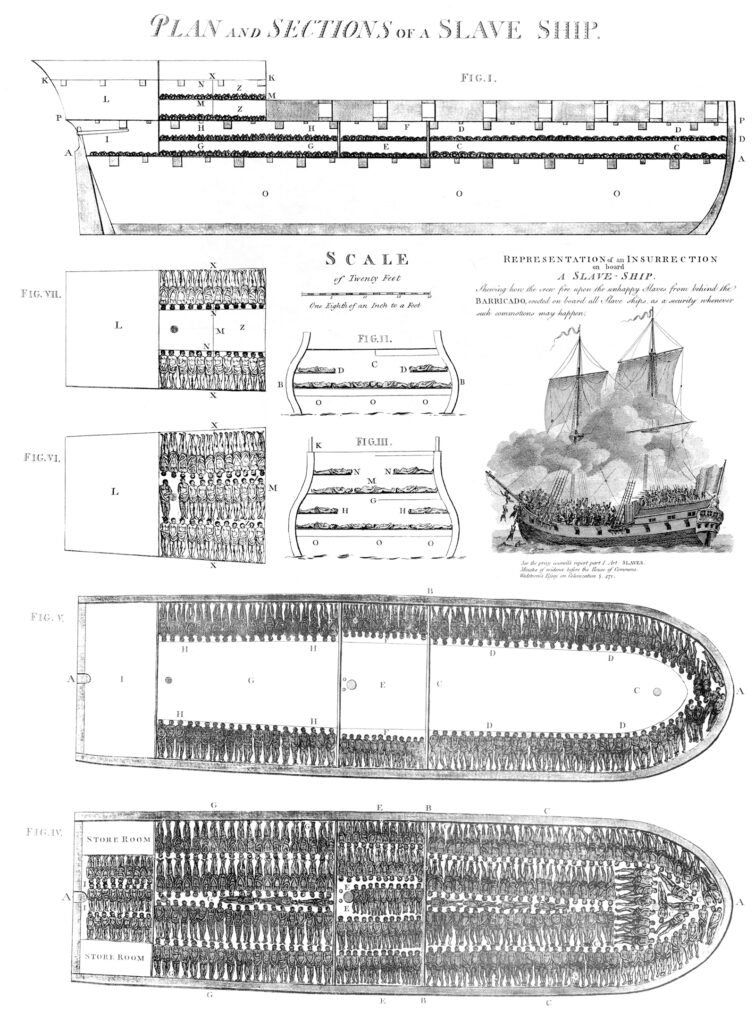

Slave Ships

Slave ships made large profits by carrying as many people as possible across the Atlantic to sell at auction. There were two methods of loading the ship:

Tight Pack

this method involved packing as many enslaved people into the hold as possible.

It was expected that some would die but a large number would survive the voyage.

A ship’s hold was cramped - only five feet high, with a shelf running round the edge to carry yet more enslaved people. People were loaded in so close together that one captain described them as being 'like books on a shelf'.

Loose Pack

Fewer enslaved people were loaded, giving them more space to lie out. More enslaved people survived the voyage, so less money was lost.

Life on board

Cramped conditions

- Enslaved people were chained and movement was restricted.

- Enslaved people were unable to go to the toilet and had to lie in their own filth. Sickness quickly spread.

- Enslaved people were all chained together. If a slave died, the body could remain in the hold for hours, still chained to other living people.

- The state of the hold would quickly become unbearable – dark, stuffy and stinking. Aside from the heat and the foul air, there could be so little oxygen that a candle would not burn.

Food

- African people were often unable to digest the food carried by the European crew, making the sickness worse. Many weakened quickly and died.

- Enslaved people who became sick were often denied food and left to die.

Mistreatment and humiliation

- The crew's treatment of enslaved people was often horrific – women could be subject to rape.

- Enslaved people were sometimes forced to dance on deck for an hour a day to keep them fit. Any resistance was dealt with harshly by floggings from the crew.

- Some enslaved people chose to take their own lives, sometimes by throwing themselves overboard, rather than endure such brutal treatment.

Sickness

Sickness on board a slave ship would often spread to the crew as well, killing many. The death rate among the enslaved people however, was horrific. It is estimated that 15–16 per cent of enslaved people died on the Middle Passage.

In 1788 British MP William Dolben put forward a bill to regulate conditions on board slave ships. He described horrors of enslaved people chained hand and foot, stowed like herrings in a barrel and stricken with putrid and fatal disorders. The Slave Trade Act, 1788 was passed and controlled the number of captives a ship was permitted to carry, according to its weight.

Dolben's Act also ordered all slave ships to carry a doctor who had to keep records about the enslaved Africans on board.

These doctors received bonuses according to the number of Africans who survived the journey. Conditions however remained appalling.

Public opinion in Britain turns against slavery and abolition Act passed

In the space of fifty years, the British slaving system was dismantled under pressure from an increasingly hostile and vocal public.

The London anti-slavery societies, drawing on networks of provincial correspondents through whom popular support for anti-slavery measures was organised, orchestrated one of the first long-running and successful campaigns to bring ‘pressure from without’ to bear on parliamentary politics.

Abolitionism was the first modern social movement.

Towards a brighter future

The Somerset case in 1772 was a turning point proving that slaveholding was illegal in Britain with Lord Mansfield confirming that slave owning was “repugnant to English law”.

By the spring of 1788, however, the slave trade had begun to acquire rather different associations to most men and women throughout England and Scotland.

Quickly, they were coming to regard the slave trade as inhumane, wasteful, horrid, and shameful, rather than as a source of national pride.

Petitions to the House of Commons requesting action against the British slave trade poured in from every corner of the country, from Norwich to Falmouth, from Southampton to the Orkney islands.

The Quakers petitioned the House of Commons in 1783 and mobilised British public opinion against Slavery resulting in the establishment of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade joining forces with William Wilberforce

Petitions and protest

By 1792, slave trade abolition had become the cause of a nation.

Perhaps half a million men and women across the country refused to consume West Indian sugar in order to show their hostility to the slave trade and slave labour.

The petition campaign of 1792 dwarfed the already impressive petition drive of 1788. In a matter of weeks, 519 petitions bearing approximately 400,000 signatures arrived at the House of Commons.

On the side of the slave trade there were four. If public opinion could have decided the question, the British slave trade would have been abolished in 1792.

Many MP’s thought that abolition would lead to a sacrifice of imperial wealth and power.

At the close of the 18th century, sustaining the plantation economy remained a strategic and economic priority.

And yet, anti-slavery also had established itself as the cause of morality, justice, and humanity within the British Isles, and, for a time, had become a source of national pride.

A shift in the political and economic circumstances would allow those impulses to claim centre stage again.

Making slavery illegal in Britain: 1787 – 1867

The campaign to end the transatlantic traffic in enslaved Africans, called Abolition, took many years.

A committee was formed in 1787 with the aim of getting the law changed to ban the enslavement of Africans, their transportation from Africa, and their sale in the Caribbean plantations.

Thomas Clarkson, from Wisbeach in Cambridgeshire, was the driving force behind this campaign. He collected evidence by going to the ports of Liverpool and Bristol and talking to sailors about the conditions on board the slaving ships.

William Wilberforce was the public face of the campaign. He was MP for Yorkshire in the north east of England, and used his position to speak out in Parliament, to push legislation and to campaign for Abolition.

Wilberforce had a model made of a Liverpool slave ship, “The Brookes”. He used it at meetings to demonstrate how enslaved Africans were packed into the ships during the ‘middle passage’ across the Atlantic Ocean from Africa to the Caribbean.

In 1807 a Bill was passed in Parliament making it illegal to purchase, transport and sell enslaved people from Africa, but slavery still existed. It was still legal to buy, sell and keep enslaved people already in the British colonies.

Enslaved men and women continued to resist their enslavement in large numbers. This encouraged campaigners in Britain to continue their anti-slavery committees until, finally, the Abolition of Slavery Act was passed in 1833.

Slavery was now illegal in all British colonies but enslaved people were not freed straight away as Parliament felt they need to training in how to be free.

Everyone over the age of six years had to complete an apprenticeship of seven years (later reduced to four) to earn their freedom.

Plantation owners and anyone who held enslaved Africans were compensated or paid money for the loss of their ‘property’. This has been estimated at around £20 million (£2.3 billion today). The freed men, women and children were not compensated for their enslavement at all.

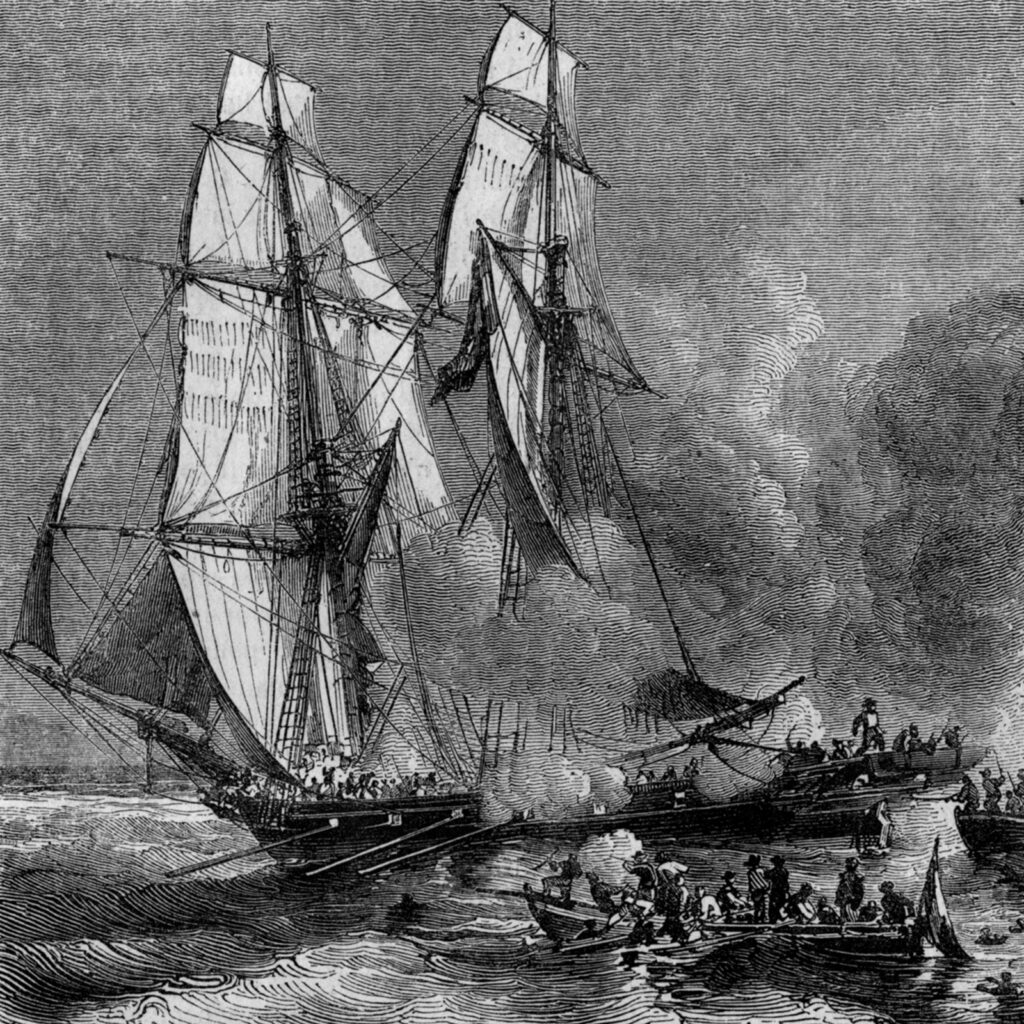

The West Africa Squadron was formed in 1807 to enforce the ban on slave trading and saved 150,000 Africans from slavery between 1807 – 1867.